I

This video has been doing the rounds: a behind-the-scenes look at the visual design of the most recent Spiderman movie Spider-man: Into the Spider-verse. I’m not a Marvel fan (just personal taste) but this is a good film. Like Deadpool (the only other comic book movie I’ve enjoyed) it subverts the genre.

If you’re a visual artist or film buff you’ll love the video breakdown (this Twitter thread is a goldmine too). The animators are really generous with sharing the techniques they used to give the film such a unique visual style.

But here’s the thing that caught my eye: Wired describes the animators’ work as creating “a new visual language” for the movie. This is interesting phrasing and - I want to argue - wrong.

It’s not that the filmmakers behind Into the Spider-verse haven’t done anything original - they have - but it’s the idea that this qualifies as a new language that’s incorrect.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this idea of visuals as language as I’ve been combing through Neil Cohn’s book The Visual Language of Comics. It’s an academic text about semiotics but it’s fairly accessible all-the-same.

Cohn argues that human beings have only three modes of self expression available to us: making sounds, moving our bodies, and making marks on a surface. This neatly contains everything from music to poetry to painting to theatre and film.

What’s interesting (to me, anyway!) is how Cohn applies two tests to these modes as to whether they qualify as a language: 1) they must convey meaning and 2) they must have rules (a grammar).

By these tests, most modes of self-expression are not a language. Painting? It can have meaning, but it has no rules. Music? It has rules, but no concrete meaning (beyond evoking emotions). In fact, Cohn says only three forms of communication pass the language test: verbal language (talking and writing), sign language, and sequential visual art (comics and films).

Calling films and comics languages though isn’t a perfect comparison. Unlike verbal and sign languages, there is no dictionary of “words” from which a filmmaker or artist builds meaning. And, as Cohn points out, what is the equivalent of speaking English in film? Most countries don’t have their own visual dialect (such is the dominance of Hollywood).

That’s why saying Into the Spider-verse has invented a new visual language doesn’t work. It ultimately uses the same grammar as all other western movies (otherwise we might struggle to understand it). What do we call this language? American Film Language? Or Western Film Language? It doesn’t have a name yet. The movie still speaks that language - albeit with a very heavy accent and some cool new slang words thrown in.

I won’t lie, semiotics makes my head hurt, but I persist with it because I feel like in understanding how language works, I might come closer to mastering telling stories visually. Hemingway mastered English grammar, so shouldn’t we master the grammar of pictures?

It’s something I’d like to keep writing to you about, if you’re interested. If I can explain it to you, hopefully I can understand it myself!

II

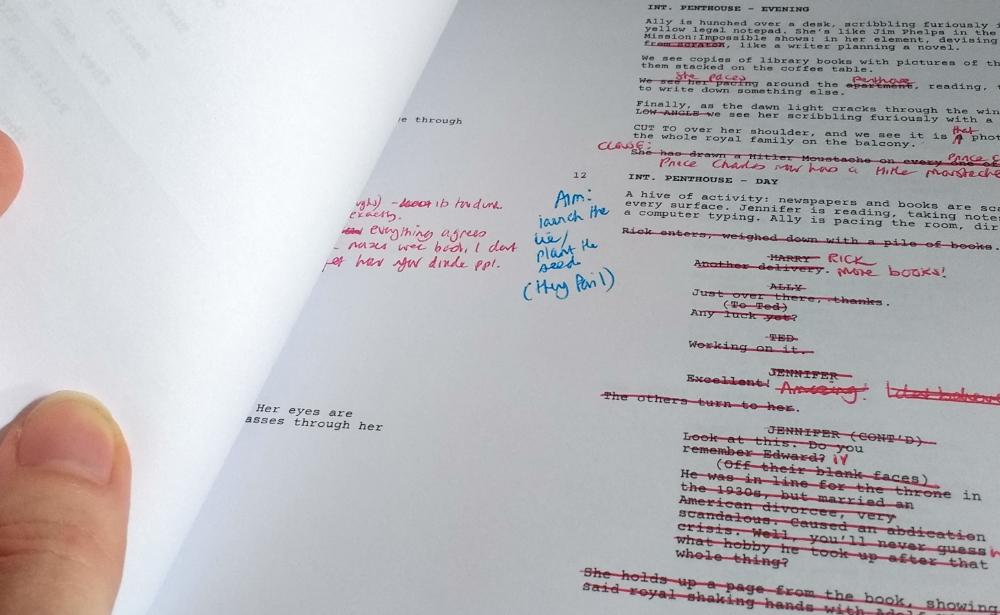

I passed a milestone on the screenplay yesterday. The second draft is now complete and I managed to shave eight pages off. It still needs a lot of work but now I’m going to give it to two or three trusted friends for feedback.

Something I have noticed in how I write dialogue: on my first pass, I fill it with lots of handle words and phrases. I start sentences with “Well…”, or “I guess” and other extraneous furniture. I also found I made characters say the name of the person they were talking to a lot, which of course we don’t do in real life.

It’s the difference between:

CHARACTER: Well Sam, I guess we could always check the files one more time.

And:

CHARACTER: Check the files again.

Striking out this fluff has made the script tighter and makes the characters feel more alive.

I think it’s natural to want to state the obvious in the first draft of a script. It’s a sign you’re not 100% confident the audience (or you!) will understand everything that’s going on. Rewriting, I am learning, is a lot about stripping away a lot of the scaffolding as you become more confident in the story’s ability to support itself.

III

The juxtaposition that invokes The Third Something does not always happen across a sequence of images; it can sometimes exist inside a single image. I’ve been thinking about this picture a lot, taken in central London on Friday.

In the foreground, a fascist, islamaphobe and popular far-right ‘activist’ addresses a crowd on a stage on Whitehall, the road that runs between Trafalgar Square and the Houses of Parliament.

In the background, the Cenotaph, the national monument built to honour those who fought and died in the two world wars.

Until another Sunday soon,