I’m in the midst of pre-visualisation for the series I am working on.

Previz, if you don’t know (or can’t guess from the name!), is where shots and images are figured out on paper before production. It’s often used for complex visual effects work, but I have found it extremely useful in my own little genre.

I’ve developed a four-stage previz process over the years.

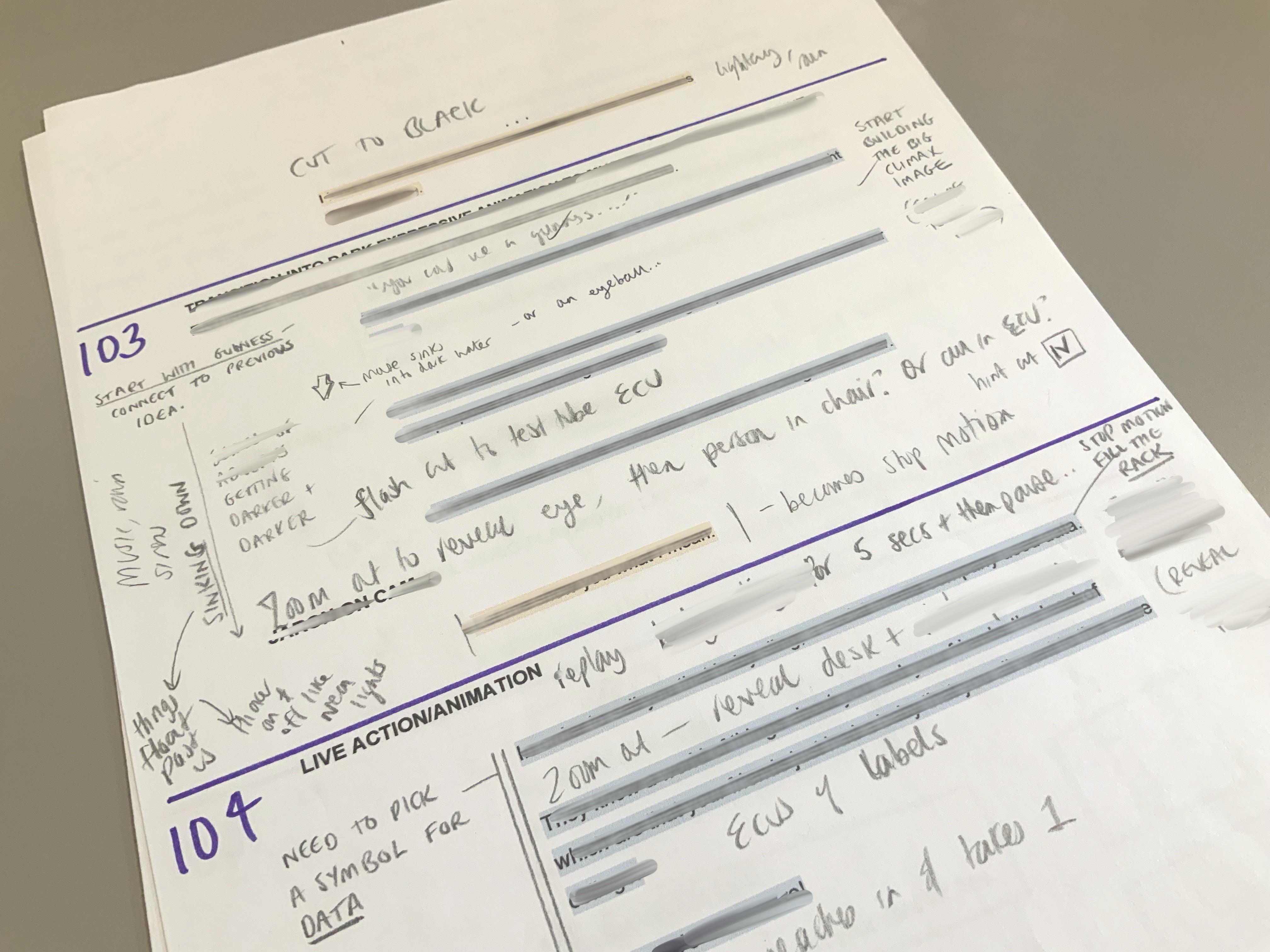

Marking up

Starting with the script, I’m figuring out what parts I want to visualise, generating ideas for concepts, metaphors and other devices. I don’t know about you, but I love scribbling over printed paper, I find it very satisfying.

Sorry I had to blank out a lot of the text!

Thumbnailing

I fill sheets of paper with little boxes and work my way through them. The purpose here is to figure out sequence: breaking ideas down into shots and working out how their assembly builds the bigger idea. It’s not so much the content of the thumbnail, but the juxtaposition 📣 that matters here. I keep the boxes small so I’m forced to draw quickly and can discard easily.

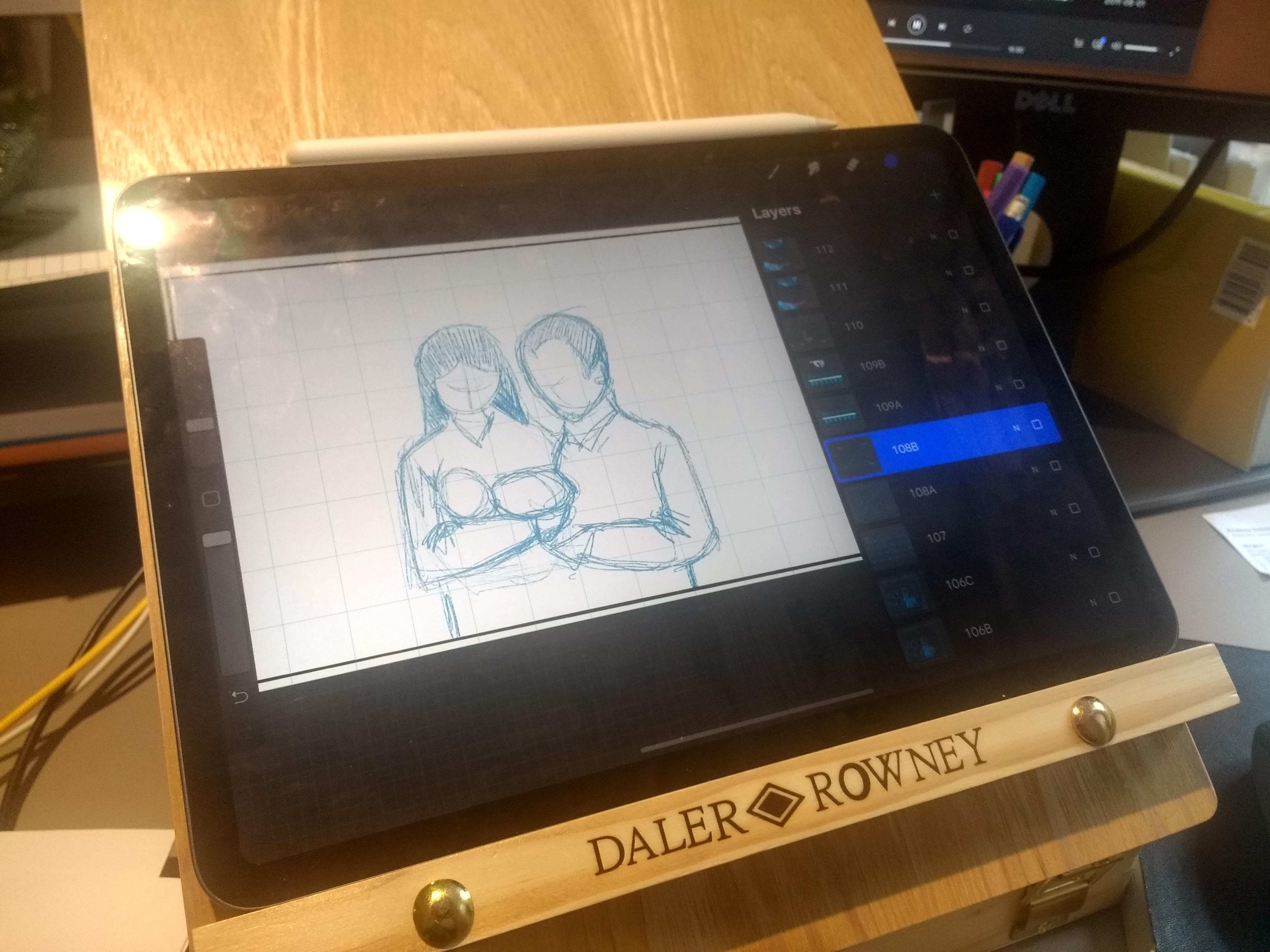

Storyboarding

I open up Procreate and draw each thumbnail out into a full size storyboard. I think more about the content now - composition, shot size - and try to render the image well. But my main goal - if other people are going to look at the boards - is clarity: can you tell what it’s supposed to be a drawing of?!

Over Wednesday and Thursday this week I managed to draw 130 boards for three episodes!

Animatic

Finally, I bring all the images into my video editing software to create a moving storyboard. Disney, who invented this process, call it an animatic. Placing storyboards alongside narration and music changes them - they become dynamic, alive, somehow.

Over the years I have learned the hard way that an image sequence that looks good on paper does not reliably come alive in the timeline. It’s much better to figure this out now, before we commit to anything expensive.

It wasn’t until my very last video essays that I started taking storyboarding seriously, but I’ve kept it up for every project since. I get that it looks like a lot of unnecessary time and effort for a little video (a lot of video makers, especially in this genre, prefer to just feel things out in the timeline).

No doubt, I would make videos much faster if I skipped previz entirely.

But I think I value this process precisely because it is slow and sticky.

It takes me somewhere between five and ten minutes to draw each storyboard. That is at least five minutes I spend concentrating on every single shot.

It is only when you stare at it for this long do you really see the image. You slow down and ask yourself “what is the purpose of this shot?” “What idea does it generate alongside the previous one?” “Is it absolutely clear?” “What if I swapped it with this other shot?”

Our system, naturally, is skewed in the other direction: towards efficiency. But whatever your craft is, look for ways to resist that, at least once in your process. Is there a place where you can intentionally apply the brakes, slow the machinery right down, and study each element for even a few minutes?

Before I dedicated time to previz I would sometimes come up with cool and clever images and juxtapositions by accident. But now they tend to happen more by design and that gives me some pleasure.

If you have any questions about my process click reply and I’ll do my best to answer them!

Last week’s letter struck a chord - I got some really thoughtful replies about being weird.

I also saw this video from popular science YouTuber Veritascium, who kind of proves my point about algorithmic monoculture by showing how YouTube creators spend a lot of energy ‘chasing’ the platform’s algorithm.

If YouTube mysteriously started promoting videos with snails in them, Derek argues, you can bet snails would start appearing in everyone’s videos.

This leaves me feeling, well, sad. In the last decade we’ve experienced a technological revolution - anyone with a phone can now express themselves in video.

When I was young this was just…impossible.

I really believed this would lead to a blossoming of creativity, an explosion of interesting forms of visual storytelling. But I think I was wrong.

Of course there are lots of talented creators out there, and some really great, interesting - even weird! - videos. But it feels that, on YouTube at least, the rewards are in satisfying the algorithm’s current preference for long, weekly, news-orientated videos with a zany thumbnail.

And, frustratingly, there are very few options outside of YouTube right now. The Verge published a really interesting piece on this last month - ‘The Golden Age of YouTube is Over’.

That’s it for this week! Don’t forget you can ping me question just by hitting reply and if you want to show appreciation for this letter you can tip me a dollar or two here.

Until another Sunday soon,