I’ve spent a good few lockdown evenings recently in the company of a four-part documentary: 10 Years with Miyazaki.

It’s a surprisingly low-fi and intimate encounter with the legendary Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki, produced by national broadcaster NHK.

It’s available — for free! — on their website and follows him as he directs Ponyo On The Cliff By The Sea (2008) and The Wind Rises (2013), one of my favourites.

If you have a soft spot for his films, animation, or just appreciate visual storytelling, then I highly recommend watching.

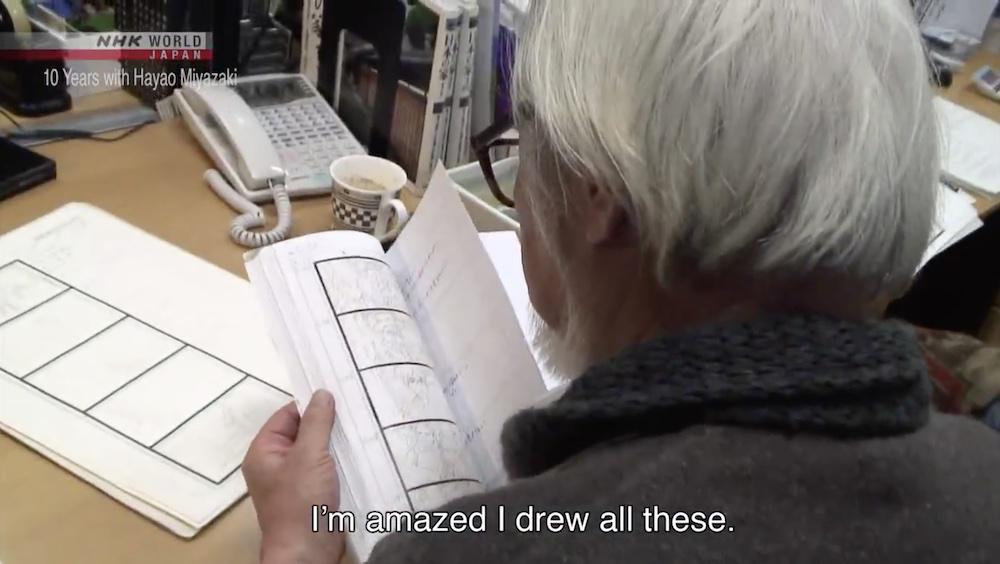

Studio Ghibli insisted that only one person shoot the documentary and so the film has the air of home movie footage as the camera operator dutifully follows an often grumpy Miyazaki, shoving the camera in his face as he sketches storyboards, an unlit cigarette drooping from his upper lip.

“Why are you filming?” Miyazaki occasionally snaps, “can’t you tell when someone wants to be left alone?”

“I’m sorry,” the filmmaker responds, and then continues filming.

There’s a whole bunch of fascinating takeaways, from Miyazaki’s morning routine (which Mason Curry writes about in detail here), to his obsession with showing rather than telling; from his heartbreaking relationship with his son Goru, captured in painful detail; and what seems to be a toxic work environment at Studio Ghibli, centred around the mercurial emotions of a ‘genius’.1

But one thing about Miyazaki’s process has stuck with me for a couple of weeks now and even changed how I create. I want to share it with you.

You don’t have to start at the beginning

Most films begin as a screenplay and most screenplays begin with “SCENE 1: EXT. STREET” — that’s where the screenwriter begins.

Miyazaki doesn’t write screenplays. Instead he works entirely in images, which someone else turns into words.

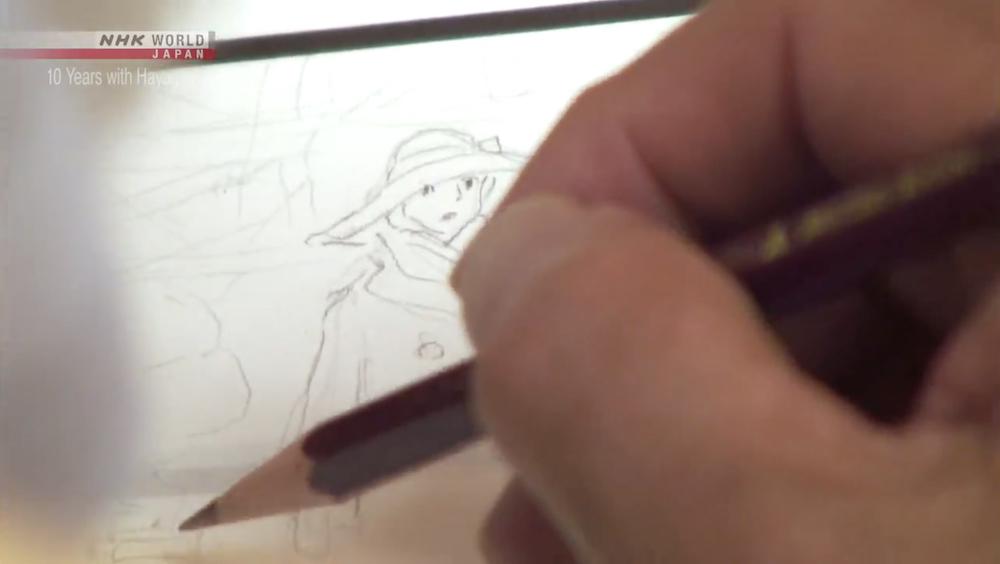

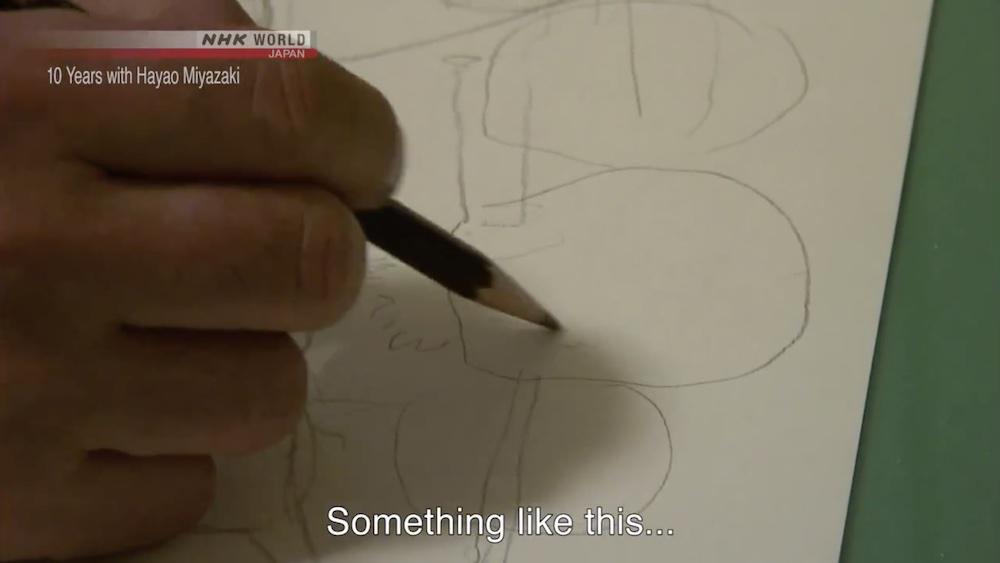

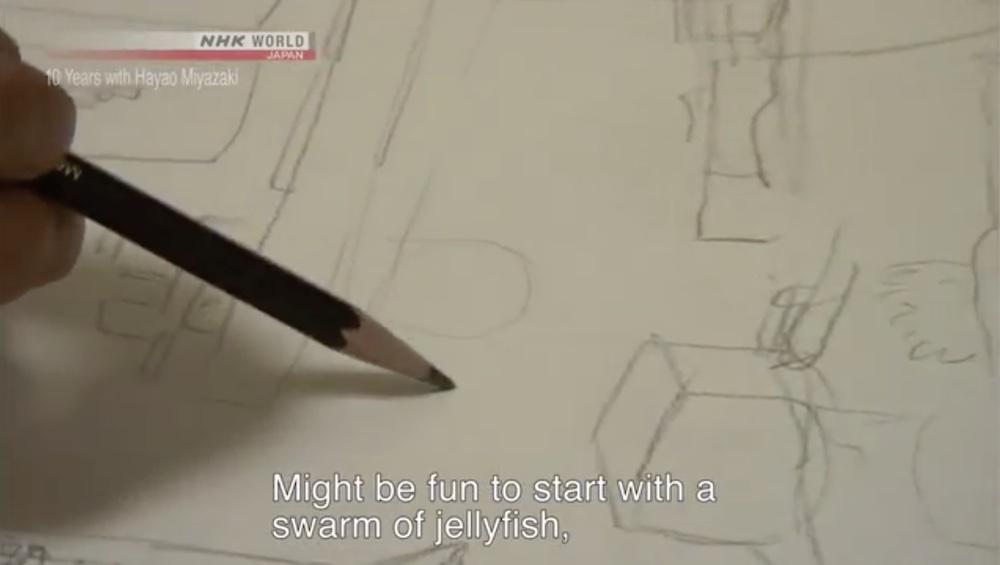

I noticed that Miyazaki draws very loose and kind of feels his way through a drawing. He’s improvising on the page.

And he starts by capturing whatever moment or image he has in his head right then.

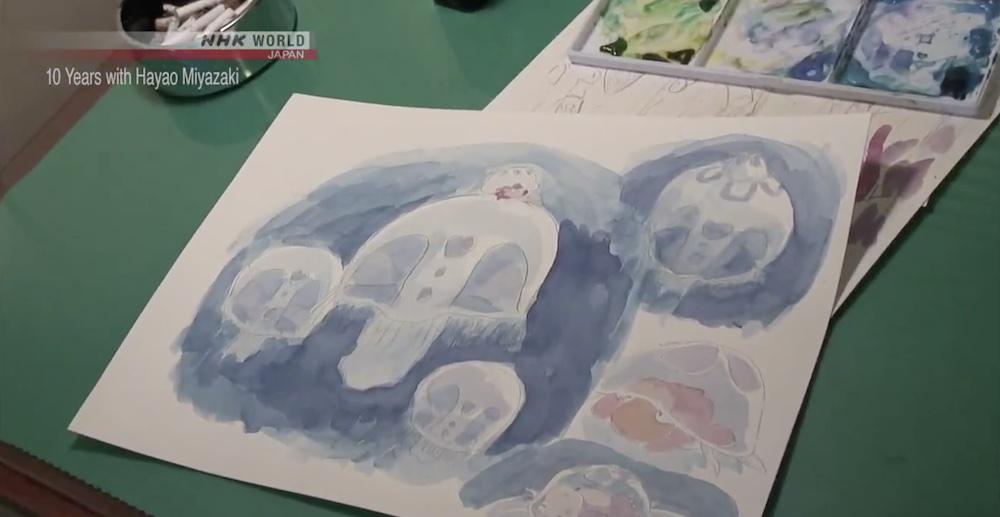

Then he paints it in watercolour. This painting captures three separate possible shots, collaged on the same page.

Here’s why this has been somewhat revelatory for me: stories don’t come to me fully formed, and they certainly don’t come to me in a convenient order. They appear as single scenes, moments, images, sometimes just feelings.

I have moments like these for a dozen different stories floating around my head, and none of them are the opening scene of whatever story they’re supposed to be.

This has stopped me in my tracks because I always kind of thought you start a story at the beginning. Why start if you don’t have a beginning?

As I watched Hayao Miyazaki painting Ponyo, I realised I don’t need to wait for the opening scene to arrive to start telling a story. I can start by exploring the images that are already in my head and just see where they lead me.

In the 10 days since I watched the documentary, I have been filling page upon page of my sketchbook with loose comics and collages, trying to capture the actions and emotions of scenes I do have. Some of them have been floating in my brain for ten years, finally getting made manifest.

Most ideas, so far, seem to have had only that one scene in them. A couple more are offering up new scenes as I clear room for them.

And as I draw, I catch myself thinking “I’m doing it! I’m drawing stories!” And more often than you’d think, I put my pencil down and feel proud of what I made.

To begin, sometimes you just have to begin — and it doesn’t have to be at the beginning.

By the way, if reading these newsletters with your eyeballs isn’t completely convenient for you, reader Eric Jung emailed me this week with a tool he’s made that converts blog posts like these into an audio playout for your podcast app, so you can listen while doing other things.

He even created an audio version of letter #95 - take a listen!

This though, might actually be to do with Japanese cultural norms, which from my understanding, don’t appreciate open debate in the same way Western societies do. ↩︎

Until another Sunday soon,