A quote I come back to often as I write visual fiction is this, from (of all people) the Elizabethan mathematician John Napier:

“If language was given to men to conceal their thoughts, then gesture’s purpose was

to disclose them.”

John Napier

💬

It speaks a truth about human behaviour both in life and art: we are rarely honest with our words, but our body language always gives us away. Our words don’t often define us, but our actions do.

In drama, characters almost never tell the direct truth to each other; they’re always misdirecting, obfuscating, exaggerating, underplaying or just plain lying to each other.

But body language is different: Our arms, legs, spine are not controlled by our conscious brain like our language centre is, so they frequently betray their owner. And while in real life, we don’t always consciously notice the body language of others, on page, stage and screen we can more easily see “through” characters to their true feelings beneath.

So as a comics artist, paralanguage – gesture, facial expression and proxemics – is essential to telling a story with multiple layers of subtext.

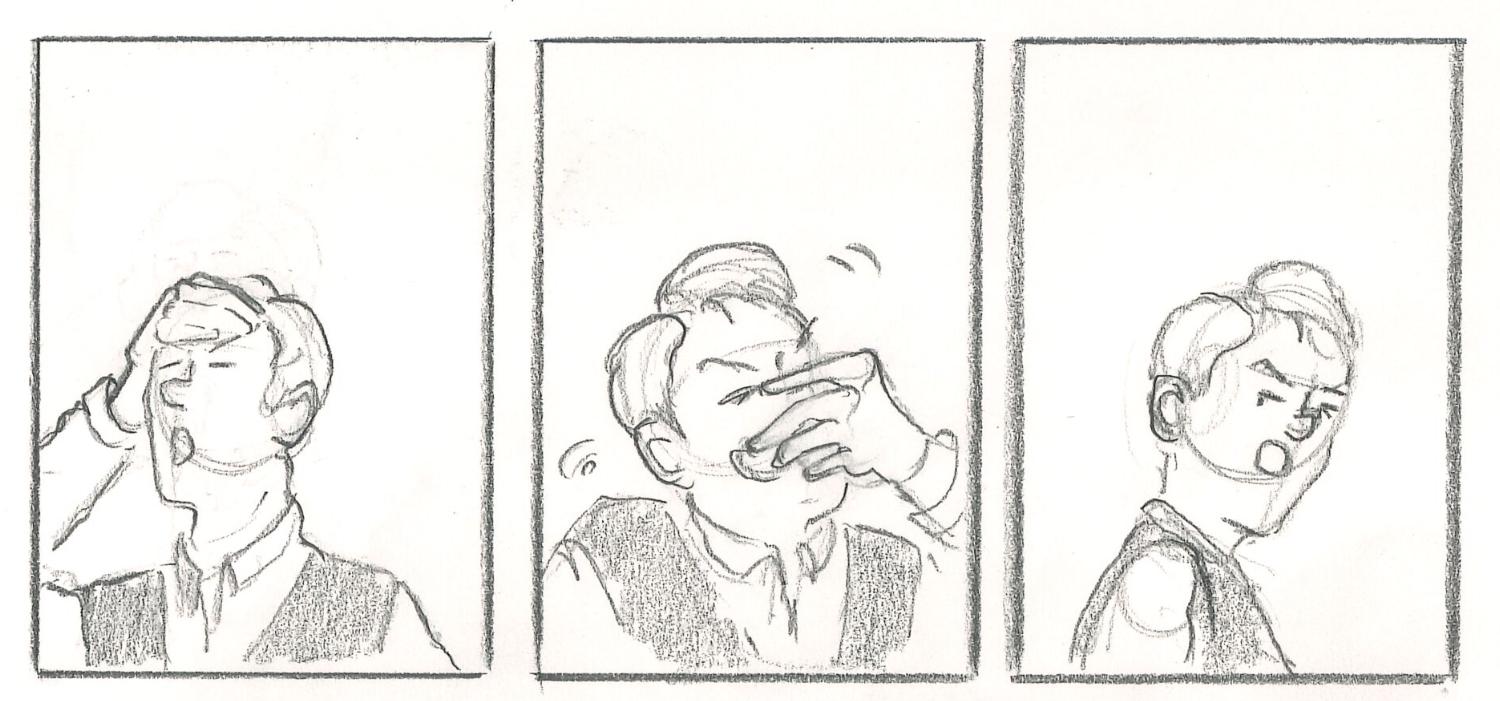

Here are some rough pencil sketches from a page of the graphic novel I’m writing. They don’t have dialogue balloons yet, but perhaps you can sense how this character is feeling, even if you don’t know what he’s saying.

As much as the scene allows, I try to avoid drawing characters standing in a neutral posture. It makes them appear lifeless and flat and contains little paralanguage for the audience to read.

Instead, I step into each character’s head at the moment, remind myself of what their intention is (even if it is at odds with the words they’re saying) and have them “act” that feeling. I make their pose as dynamic and active as possible and, where appropriate, vary the angle and composition to avoid drawing them dead-on.

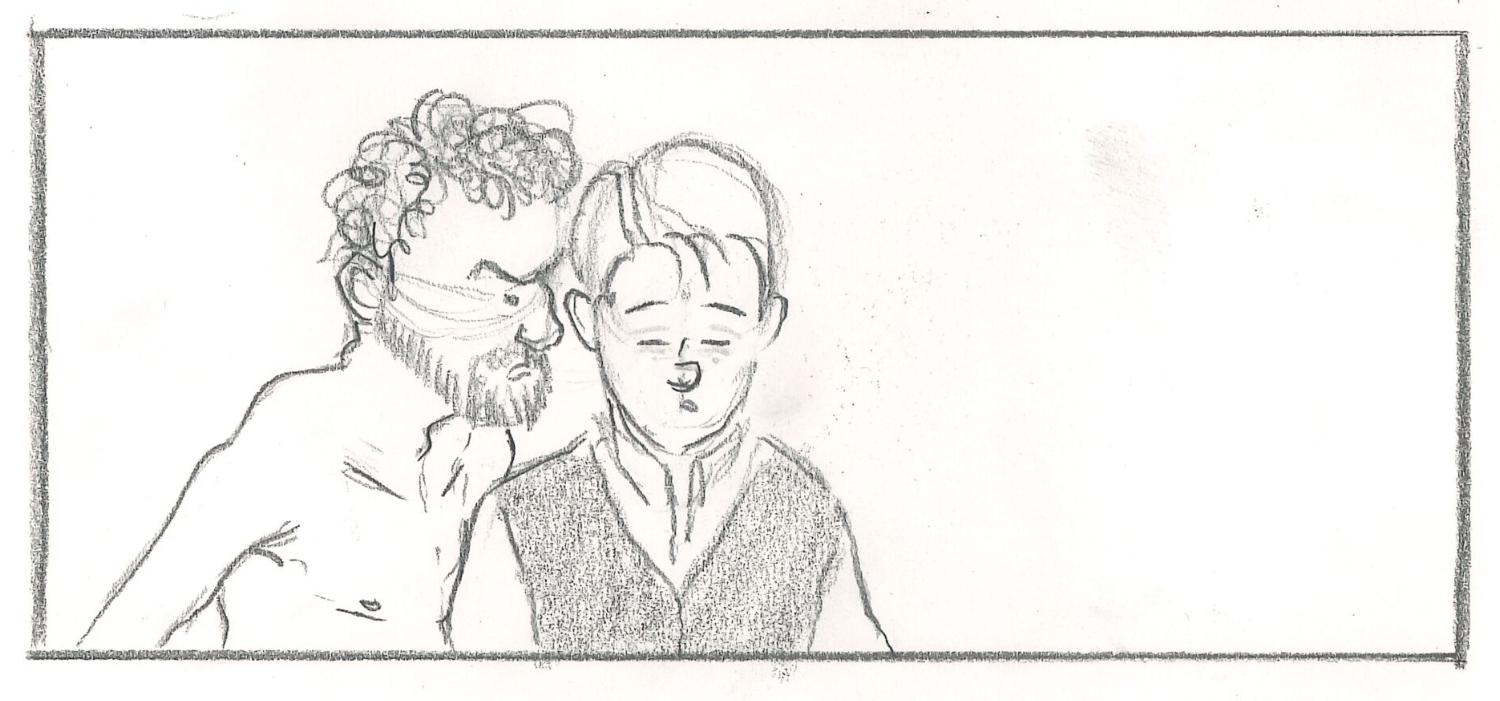

Here’s another roughly drawn panel. Again, without dialogue balloons, can you tell who’s in control?

Proxemics (the distance between characters or objects in a scene) can be used to convey lots of subtextual information, including power dynamics and conflict.

Paralanguage is what semioticians would call an index sign: it indicates something you cannot see through something you can see.

You can’t “see” wind. You can’t draw it or film it. So how do we know it’s there? By the effect it has on other things: The rustling leaves, the spinning weathervane, the mid-air ballet of the plastic bag.

In the same way, body language allow us to “see” a character’s invisible feelings, by the effect emotions have on their bones and muscles.

It’s one of the best tools we have to make the invisible, visible — and that’s the job description!

Until another Sunday soon,