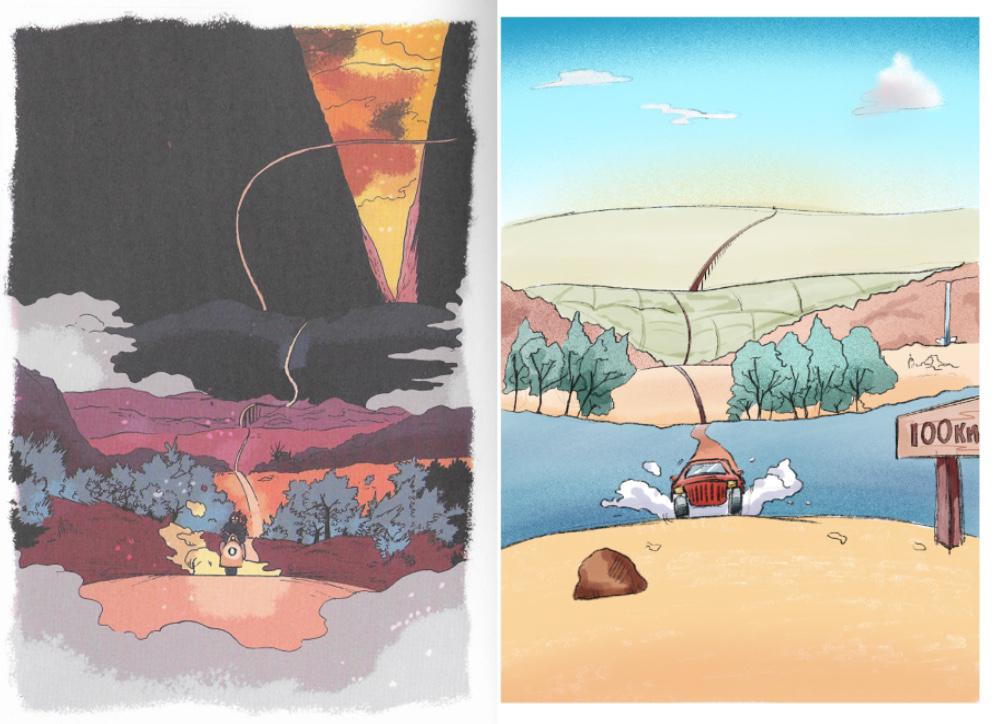

A panel from _Are You Listening?_ by Tillie Walden (left) alongside a recreation by me (right)

I recently finished Tillie Walden’s new graphic novel Are You Listening?

I understand she made it very quickly (having already produced two others by the age of 23 😲) but it’s a sophisticated piece of work and worth your time.

The two main characters are both gay but there is no attempt at any kind of romantic or sexual story between them. They are - shock, horror! - just friends. It seems no writer is capable of putting two sexually compatible people in the same story without making them get it on, so this was refreshing.

Secondly, the story takes place against a bizarre and mysterious backdrop of unusual weather, magic cats and sinister pursuers. I love it when graphic novels lean into the fantastic in this way - it is a real advantage of the form over film. As much as I enjoyed the hyper-suburban Sabrina by Nick Drsano, it was mostly panels of people talking while sitting down, and you wonder: why not just film this?

Above, on the left, is one of the final panels in Are You Listening which inspired me to attempt my own multilayered landscape road trip picture.

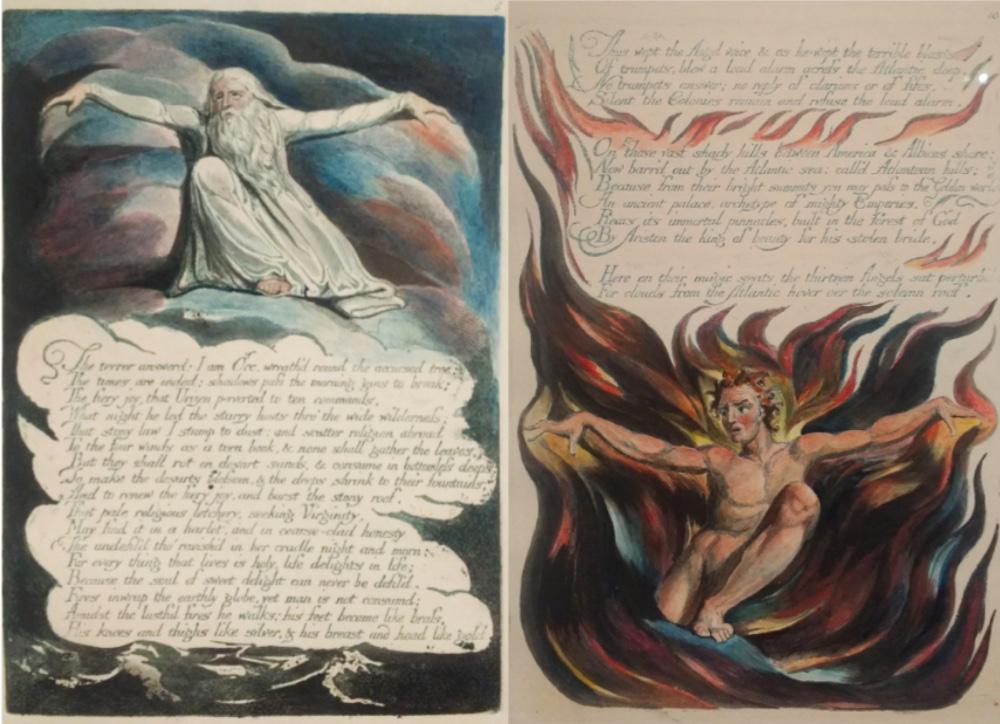

There’s a really great William Blake exhibition on at the Tate Britain museum in London right now - we spent nearly three hours in there without seeing the time.

As I wandered past his elaborate and intricate plates of poems and images, I wondered what Blake, who was almost completely unrecognised in his lifetime, would have thought of hundreds of people from 200 years in the future queuing to see his work.

To a 21st-century freelancer, his career feels familiar: he struggled with the never-ending conflict of balancing his creative ambitions with the need to make a living; he had bad clients who cramped his style and didn’t pay him properly; he self-published passion projects only to sell just a few copies.

Hands up if you’ve been there… 🙋♂️

He developed a process that allowed words and pictures to be printed together on the same page and, arguably, took western culture a step closer to the comic.

Speaking of comics, the culture row about the dominance of Disney/Marvel spectacles continues.

You might have seen Martin Scorsese’s op-ed in the New York Times earlier this month, where he doubled down hard on his criticism of the genre:

The situation, sadly, is that we now have two separate fields: There’s worldwide audiovisual entertainment, and there’s cinema. They still overlap from time to time, but that’s becoming increasingly rare. And I fear that the financial dominance of one is being used to marginalize and even belittle the existence of the other. For anyone who dreams of making movies or who is just starting out, the situation at this moment is brutal and inhospitable to art. And the act of simply writing those words fills me with terrible sadness.

I balk a little bit at millionaire directors lamenting the ‘death of cinema’ when they have not been to a normal cinema (that isn’t in their own mansion) in decades.

(Try paying £15 in a dirty Odeon that smells of sweat, rips you off for a box of popcorn and makes you sit through 30 minutes of commercials - and then tell me how great the big screen is).

But Scorcese’s scorn pales next to these words from comic book artist Alan Moore this week. Get a load of this:

I think the impact of superheroes on popular culture is both tremendously embarrassing and not a little worrying. While these characters were originally perfectly suited to stimulating the imaginations of their twelve or thirteen year-old audience, today’s franchised übermenschen, aimed at a supposedly adult audience, seem to be serving some kind of different function, and fulfilling different needs. Primarily, mass-market superhero movies seem to be abetting an audience who do not wish to relinquish their grip on (a) their relatively reassuring childhoods, or (b) the relatively reassuring 20th century. The continuing popularity of these movies to me suggests some kind of deliberate, self-imposed state of emotional arrest, combined with an numbing condition of cultural stasis that can be witnessed in comics, movies, popular music and, indeed, right across the cultural spectrum. The superheroes themselves – largely written and drawn by creators who have never stood up for their own rights against the companies that employ them, much less the rights of a Jack Kirby or Jerry Siegel or Joe Schuster – would seem to be largely employed as cowardice compensators, perhaps a bit like the handgun on the nightstand. I would also remark that save for a smattering of non-white characters (and non-white creators) these books and these iconic characters are still very much white supremacist dreams of the master race. In fact, I think that a good argument can be made for D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation as the first American superhero movie, and the point of origin for all those capes and masks.

Wowza.

Next week I’m probably going to write to you about the possible futures for this newsletter - we are barely a month away from the end of the experiment!

Until another Sunday soon,