I’m very excited about today’s guest letter.

It comes from Michi Mathias, an artist and illustrator in Brighton, on the south coast of England. A few years ago, I wanted to give C a replica of an illustration from one of her favourite childhood books. Searching for local artists, I found Michi and commissioned her to create it.

Michi recreated the picture from a photograph, beautifully capturing the original illustrator’s fine pen and brush work. The picture has pride of place in the living room.

So when Michi wrote in and offered to write a guest letter about creating her graphic novel, I said yes right away. Over to you, Michi!

Panel by panel storytelling

I’ve often started projects without knowing exactly how to finish them.

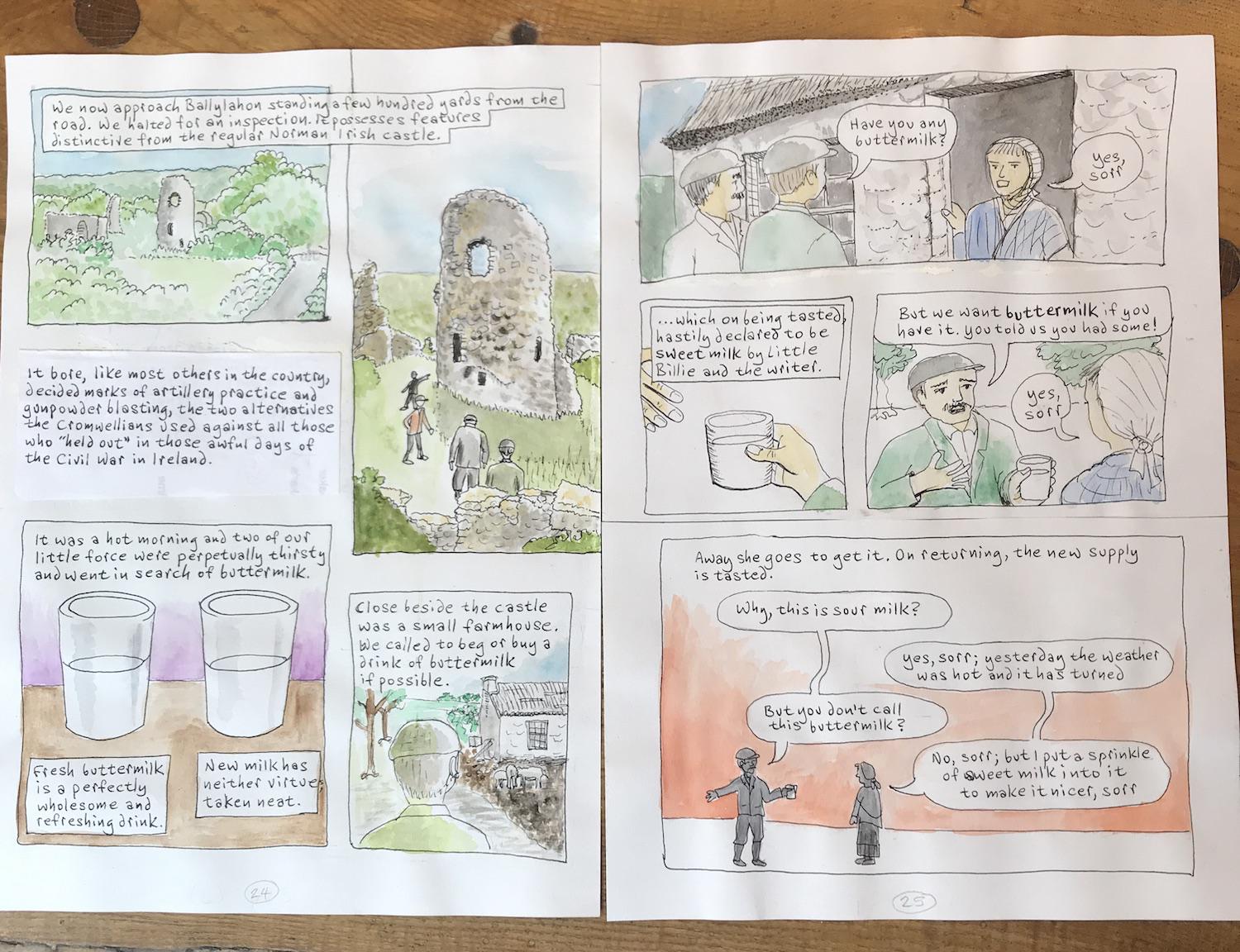

This was never more true than when I took the leap of making a graphic novel adaptation of an 1890s book I had fallen in love with — even though I’d only recently returned to drawing after a long hiatus and had barely started making even short comics.

After much re-reading and note-taking, trying to figure out how to begin, I eventually pencilled fifteen pages in a sketchbook, but very quickly saw other ways I wished I’d done it. Repeatedly erasing and redrawing panels was too awful, and anyway I couldn’t see how these scribblings would ever end up as a finished book.

Luckily, two helpful clues appeared.

At a talk I attended on making graphic novels, the speaker described how he writes on loose pages in ring binders when he plots stories. Then a friend told me about drafting comics digitally with InDesign, dropping sketches and notes into panels on screen and moving them about as needed.

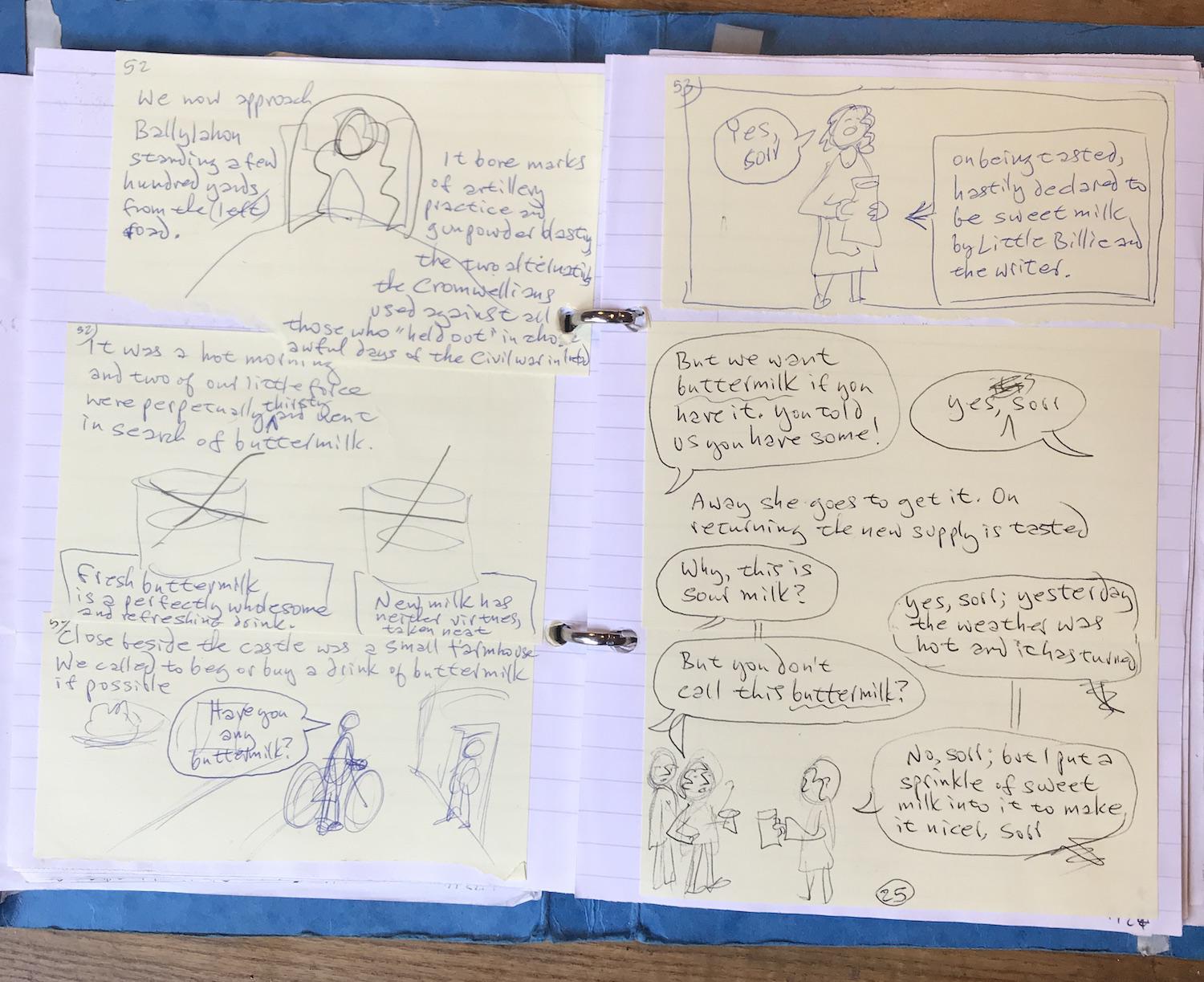

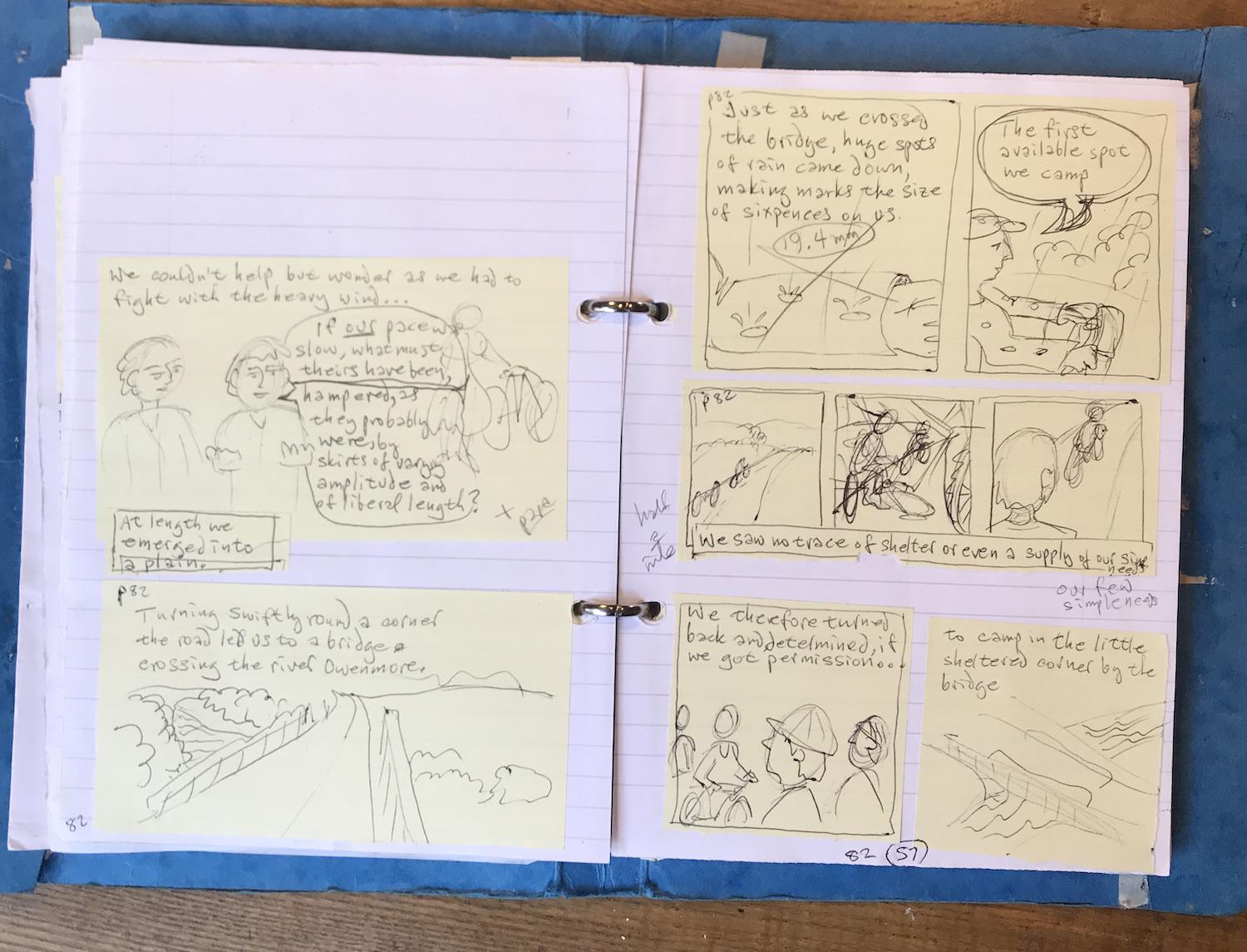

I suddenly realised I could combine these two techniques: I could draw panels on post-it notes, placing them on looseleaf pages in a binder. I tried this out with a four-page comic, and it worked beautifully when I wanted to add more story between panels, stretching the action over to the next page.

So finally I was able to progress without having to make firm decisions.

Post-it note panels were moved, re-drawn, combined, and divided as I figured out page layouts. And I moved pages again and again as I tried to find the best sequence for telling the story, changing the order of sections or whole chapters.

How many pages I was in for? I needed to know, so I thumbnailed my entire text: about 140.

But everyone has their own method.

One experienced graphic novelist I know drafts and then draws each page of her final artwork one at a time, and finds out how long her book will be when it comes to an end. Another friend plans her entire story using tiny, perfectly detailed thumbnails.

There were numerous scenes I hadn’t a clue how to draw, so I put the text as a placeholder and left the images for later.

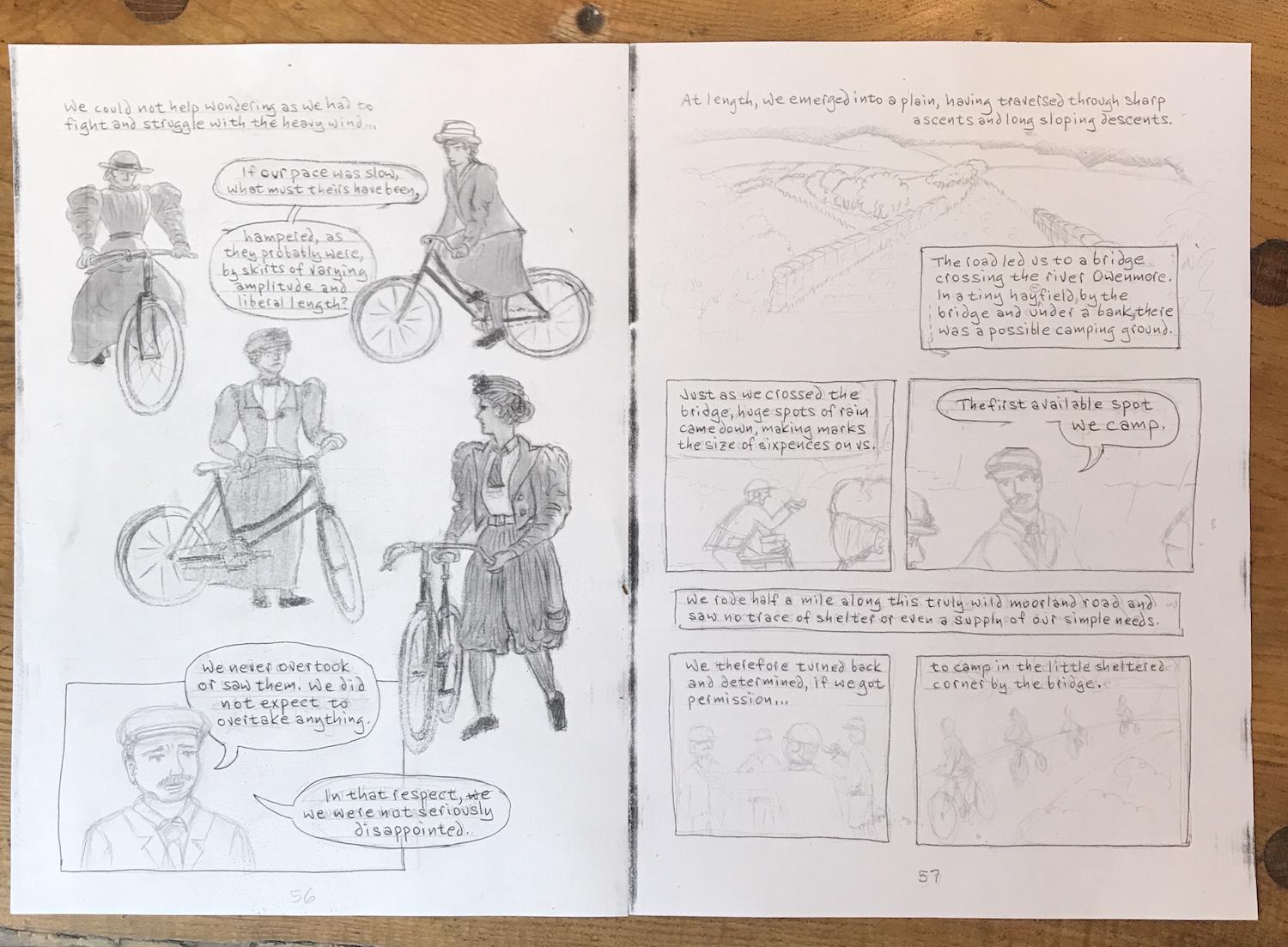

I couldn’t have included much detail for some as I didn’t yet know how much I didn’t know: what did everything look like in 1897? Not just the bicycles and the clothing, but the streets and cottages, the tin openers, the mail cars — everything! Little did I realise I would end up searching through old tailoring magazines at the British Library or visiting a cycle museum in mid-Wales, or spending untold hours online looking at late Victorian photos. Or building little paper and clay models to draw from.

Converting such rough post-it notes to a pencilled draft is the longest, most difficult and important part. How does each page look in relation to the ones before and after? Is the last panel on the right-hand side suitable for the page turn? Does the text fit the panel; is there too much on the page?

I chose to ink and watercolour some of these at the draft stage so I could see how the final artwork would look. Just as well, as I had to buy three or four waterproof inks before settling on the only one which dries quickly but also flows from the fountain pen nib without an infuriating half-second pause.

It’s been over three years of intermittent work, and it’ll be at least two more.

Would I have started if I knew then what I know now? Yes, I still think so!

Michi, thanks so much for your letter.

In any sequential art project, the panel-by-panel (or shot-by-shot) choices are in many ways how the story is told. Starting with a close up and then a wide shot can radically affect the audience’s response, as opposed to starting with a wide shot followed by a close up.

What I love about Michi’s method is how it makes it so easy to play around with different combinations without committing to anything. You have to move these pieces around with your hands to feel how they work!

Michi has another great project on the boil: a graphic recipe book of vegan dishes, to be published next spring. It looks excellent!

Until another Sunday soon,